One of the hallmarks of a quality software house is the time and effort they spend in the analysis stage. But what does that look like from the inside? Join us as we examine a variety of points of view, ways of solving problems, and project requirements, with useful advice for the daily work of the business analyst.

Laying the firmest groundwork

The decisions that are perhaps the most crucial for a project’s success are the ones taken at the very beginning—who will be involved in the project? When the client provides their requirements and defines what they need, we ask and confirm who has the greatest stake in the success of the project. That is the information you need to make good, solid choices about the team’s members. If your client is also supplying some members to the team, you will want to be sure that they and their superiors are on the same wavelength when it comes to the importance of the analysis. When only part of the team is fully engaged in analyzing the project, the project will suffer.

Example 1: a pharmaceutical client

Let us take as an example a project we did for a pharmaceutical company. We created a target group of key people from each department that stood to gain—or have some aspect of its work affected by—the results of the project. There were also some areas and departments for which the project was of minor importance, so we created on-demand access channels for them.

One particularly effective task was booking analysis meetings an entire quarter in advance. Even though such meetings are likely to need rescheduling, booking early sets up a condition of commitment and an understanding that the analysis is a necessary stage and crucial to the success of the project. It must be understood that when it comes to knowledge work, meetings do not take team members away from work—rather, meetings are work.

Leadership is best provided by someone with seniority in the client’s organization, someone who can provide a driving force. This is important when organizing and mobilizing the various stakeholders on the client side to ensure that essential team members step up and fulfill their roles. Project managers know their employees. By being present and participating in the meetings themselves, they know who can step in when needed, such as when there is an unanticipated absence or to provide additional expertise. When a tool, device, or system becomes useful, the project manager is best placed to provide the necessary access.

Experience has shown that employees in the pharmaceutical industry are typically well-prepared for projects. They are well-organized, and they get deeply involved in workshops. Their IT skills may not be so well-developed, so it is important to make sure they are involved in the needs analysis and that they are open to learning whatever skills they may need.

Example 2: an aviation client

For a second example, we can look at an interesting project we did for an aviation manufacturing company. We created bespoke software for use in the client’s production process. As you might imagine, for something with so much potential to alter the pace of production, it was closely watched by the firm’s highest-level executives. That kind of awareness certainly makes a difference at all stages of the project.

In this particular case, there was the issue of ensuring that the employees who work in production could be involved in every stage of the project, since of course they would be busy on the production line. There are two complementary ways to achieve this:

- appoint a representative of the production employees to attend project meetings and report back to their group, and

- engage the team members in observation and shadowing for the most direct understanding of the firm’s production process.

Indeed, the employees’ perspective was highly valuable, even essential, for the success of the project. They had the clearest awareness of what was needed, not to mention their precise instructions for improving the application’s user interface.

These were our steps:

- Gathering and analyzing information about the client’s needs.

- Creating a “high-fidelity” prototype (that is, one that looks and feels as polished as a final version).

- Collecting and analyzing comments and suggestions from the end users—the employees on the production line.

- Adapting and refining the project requirements in light of the comments and suggestions.

- Beginning the project design.

To some, this sequence of events may seem to impose a heavy time burden on the project. In fact, it saves time because the production phase is significantly faster. There are fewer surprise issues, less time spent on explanations, and fewer unnecessary interruptions. And there is reduced cost for the final implementation because the project team is less involved—the production employees already know a lot about the project and feel invested in it.

Example 3: a financial client

A particular challenge for the analyst is doing a project for a state-owned institution, such as a financial institution we worked with. Laws and a state organization’s own regulations, which may change quickly and sometimes without warning, make for unique working conditions.

But the project’s stakeholders remain the most important aspect of a successful project, not the industry or institution. Their help, and especially the support of decision-makers, is essential for predicting, reducing, or eliminating potential barriers, and without this the analysis process could get stuck.

Large state institutions typically create reams of documentation; wise analysts will likewise be thorough, though concise, with their records. Create a summary of what was agreed in every meeting and the next steps for the individuals present. Once the analysis is complete, you can create the overall project documentation, which should have official approval before moving out of the analysis stage.

This is not always easy, because even when an official has personally put time and effort into the analysis, they may not be willing to put their name on it. They may feel that this would close the project to later changes and adaptations. You will nonetheless want to press the issue before going forward because it truly is worth the effort to get the client’s sign-off.

Therefore, be sure to have strong support from both your legal department and the client’s.

A bit of advice

As you can see, the success or failure of a project hinges quite a bit on the quality of the analysis done at the beginning, no matter who the client is. Gathering complete information on project requirements and expectations, good organization of work time, and a clear understanding of the stages in producing the final version are all essential components of a valid analysis. Otherwise, additional costs may be incurred at the end in hopes of making a success from probable failure.

So here is some useful, experience-based advice.

1. Take time to form a deep understanding of the context the project will be implemented in.

Read about and talk to people with long experience in your client’s industry. You will need to be familiar with any unique terms and jargon likely to be used by the stakeholders. Also, research if and how other firms in the industry have met the challenge faced by the issue your project aims to solve. If it has not been solved, were there conditions that the firms could not overcome?

Also, any text materials produced by the firm and, if possible, resources they use on a regular basis could help you get a well-rounded idea of what information the employees work with on a daily basis.

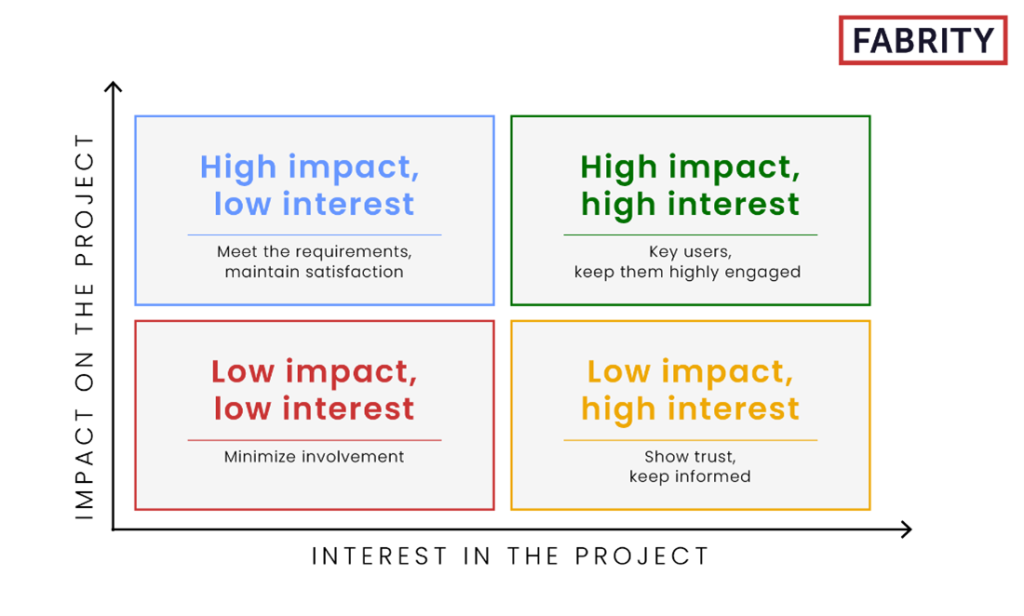

2. Create a Power-Interest Grid of the people surrounding the project.

As mentioned earlier, knowing who the project’s stakeholders are is a vitally important part of any project’s analysis stage. This is not just taking names and job titles, however. Since each stakeholder has a different amount of interest in, benefit from, risk from, and also influence on the process and the outcome, a Power-Interest Grid will help you visualize these complex interpersonal relationships (see Figure 1 below). It is drawn as a graph, with interest on the horizontal axis and impact on the vertical axis. Each stakeholder appears as a point on this graph.

This graph will clearly indicate who the key players are who, as we have noted, are quite useful to have deeply engaged in the project. Spend as much time with them as possible, and less with the people with low decision-making power and low interest. You can decide whose needs to pay most attention to and effectively manage relationships.

Fig. 1 A Power-Interest Grid for business analysis

3. Organize a meeting to read over your business analysis together.

This will be a long meeting that may be difficult to “sell” to the stakeholders. However, merely asking them to read your documentation is usually pointless.

A lot of good can come out of such a meeting. This is an opportunity for the client to correct any misunderstandings, inaccurately reported needs, or simple informational gaps. The stakeholders have the opportunity to ask for clarification on any items in the analysis that they do not understand. Altogether, your team and the stakeholders will gain interpersonal accountability, knowing not only their own role but also how others’ roles depend on them.

Finally, this is a great opportunity to obtain the client’s final confirmation and formally close the analysis stage. It goes a long way toward increasing everyone’s satisfaction.

Business analysis in software development—the wrap-up

While technical know-how is necessary for effective analysis, experience with projects makes it clear that soft skills are equally necessary. So, choose your stakeholders carefully to make your next software development project a success.